Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full creditsAdvance tickets are recommended and are available for visits through July.

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view,

View full credits

Tschabalala Self,

View full credits

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view,

View full credits

Tschabalala Self,

View full credits

Installation view,

View full credits

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view, TschabalalaSelf:OutofBody,InstituteofContemporaryArt/Boston,2020.PhotobyCharlesMayer.Courtesyoftheartist.©TschabalalaSelf

View full credits

Installation view,

View full creditsTschabalala Self (b. 1990, Harlem, New York) creates large-scale figurative paintings that integrate hand-printed and found textiles, drawing, printmaking, sewing, and collage techniques to tell stories of urban life, the body, and humanity. The artist’s first Boston presentation—and her largest exhibition to date—will include a selection of paintings and sculptures that represent personal avatars, couplings, and everyday social exchanges inspired by urban life. Together, they articulate new expressions of embodiment and humanity through the exaggerated forms and exuberant textures of the human figure, pointing to its limitless capacity to represent imagined states, memories, aspirations, and emotions. Yet Self’s characters possess an ordinary grace grounded in reality: they are reflections of the artist or people she can imagine meeting in Harlem, her hometown.

Based in New Haven, Connecticut, Tschabalala Self (b. 1990 in Harlem, NY) was raised in Harlem as the youngest of five. She grew up observing the textures and pace of metropolitan life, with a keen attention to the surfaces that surround and clothe our bodies—whether carpet or curtains, fashion, or salvaged textiles that contain the spirit of use. The creative repurposing of material, along with the self- expression and self-possession of black women—including her mother’s innovative transformation of fabrics into dresses—inspire her work. The paintings and sculptures on view, dating from 2015 to the present, convey a multidimensional humanity, from strength and vulnerability to sexuality and boredom, shaped by methods of abstraction.

Self mobilizes eclectic techniques and materials to create animated figures that express interior states, the social energy of everyday encounters, and the potential for action. The artist places the figure of a black body imaginatively, aspirationally, and introspectively in relation to its historical representation as a symbol of property and a foil for whiteness. Combining her training in printmaking with painting, sewing, and collage, she assembles her artworks from hand-printed canvas, found textiles, and fragments of old paintings. Multiplicity—which the artist defines as the notion that we are all made up of fragments of memories and identities—is central to her formal vocabulary. As the artist notes: “You are the sum of your experiences, but you also absorb … all of the different ideas and experiences of others. My process mimics this phenomenon.”

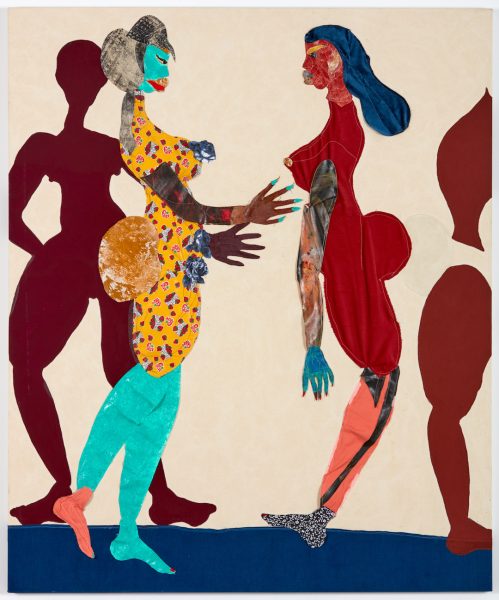

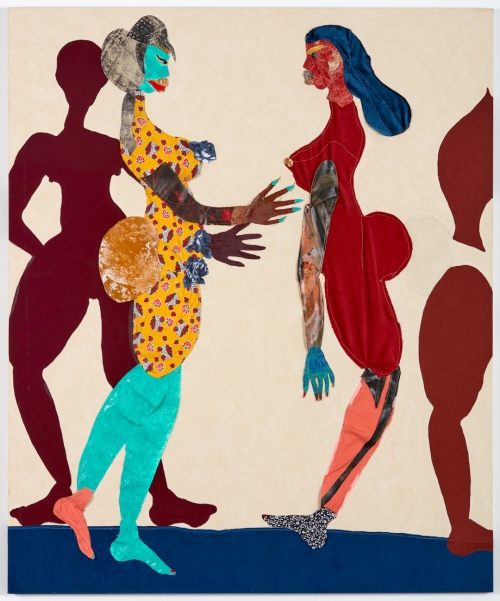

Out of Body, 2015

Oil and fabric collage on canvas

Acquavella Galleries

Out of Body encapsulates the artist’s practice at large, in respect to one woman constructing her own avatar: the figure on the left leans with intention toward another figure, who mirrors her. The figure on the right resembles a doll, or a puppet not yet animated—perhaps awaiting its activation by the figure on the left, whose body is articulated in bright colors and flower blossoms. Perhaps this is a self-portrait of the artist who, in her self-assuredness, confidently fashions the shapes and pieces at hand into lively figures. To render the textured appearance of the woman’s hair and buttock, Self used collagraphy—a process that entails pressing an inked plate, assembled from diverse materials, onto canvas. Doing so enabled her to use printmaking techniques on the grand scale of painting, a combination of visual expanse and experience not possible within either single medium. The sewn line is also significant: here, it primarily affixes the figure to canvas, but hints at later works, in which it becomes an expressive, drawing-like gesture, activating sculptural rumples and folds in the fabrics that make up the figure.

Bellyphat, 2016

Painted canvas, fabric, oil, acrylic, and Flashe on canvas

Collection of Craig Robins

Holding her protruding abdomen, the female figure in Bellyphat is a vision of anticipation and affection. Pausing mid stride across a checkered floor, she turns her head toward the male silhouette that rises from her footstep in a posture that is both performative and self-possessed. As the artist notes of such couplings in her work: “The male characters are continuations of the female persona. They are there to help tell the story about her.” The woman’s thigh is a print of an architectural facade—a reference to Louise Bourgeois’s series of paintings and prints from the 1940s entitled Femme Maison (literally, “woman house”). The concept, in both artists’ work, suggests the habitat of the self as composed of an exterior to be contemplated by others and an interior to be discovered. Self, who in the artist’s words, grew up in a “women heavy” household, emphasizes the work and emotional labor that women do to both nurture and contain the lives of others.

Louise Bourgeois, Femme Maison, 1946–47. Oil and ink on linen. 36 × 14 inches (91.4 × 35.6 cm), Collection Louise Bourgeois Trust, New York © The Easton Foundation/VAGA at ARS, NY

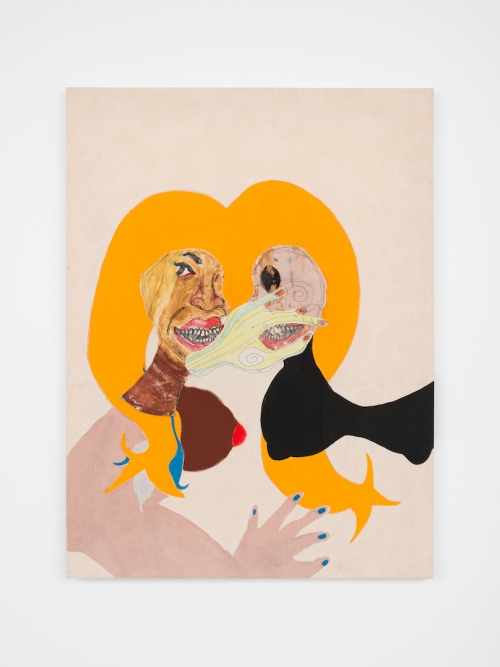

Chop, 2016

Painted canvas, Flashe, acrylic, and colored pencil on canvas

Easton Capital/John Friedman Collection

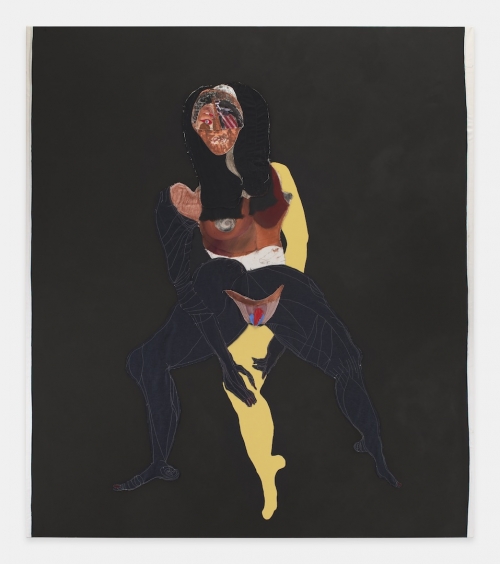

No, 2019

Fabric, acrylic, Flashe, and painted canvas on canvas

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

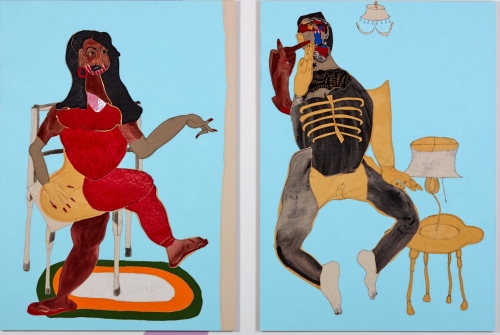

Thank You, 2018

Acrylic, watercolor, Flashe, fabric, crayon, colored pencil, oil pastel, pencil, hand-colored canvas, and plastic bag on canvas

The Art Institute of Chicago, promised gift of Nancy and David Frej

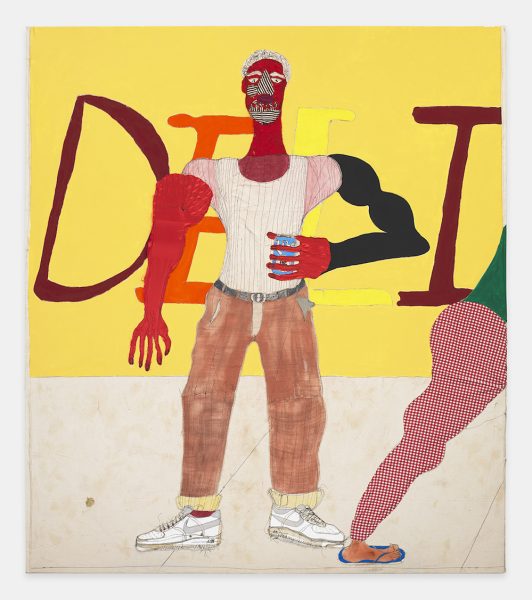

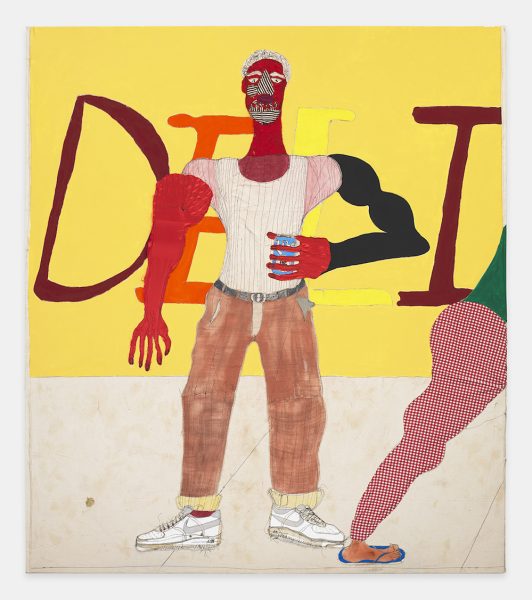

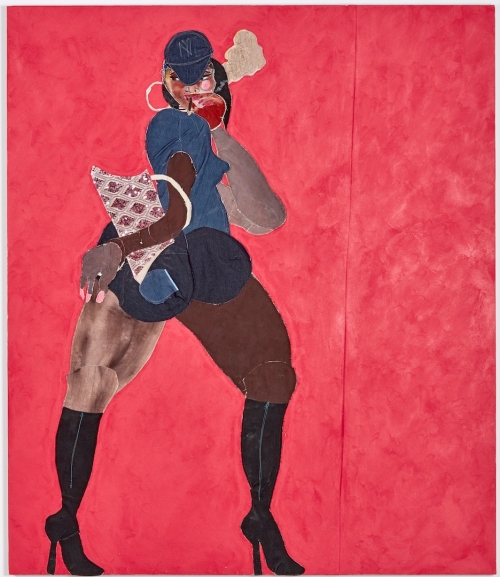

Dime, 2019

Fabric, acrylic, Flashe, and painted canvas on canvas

The Studio Museum in Harlem; Museum purchase with significant funds provided by Komal Shah and Gaurav Garg and the Acquisition Committee

Spat, 2019

Acrylic, fabric, paper, dyed canvas, painted canvas, and raw linen on canvas

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

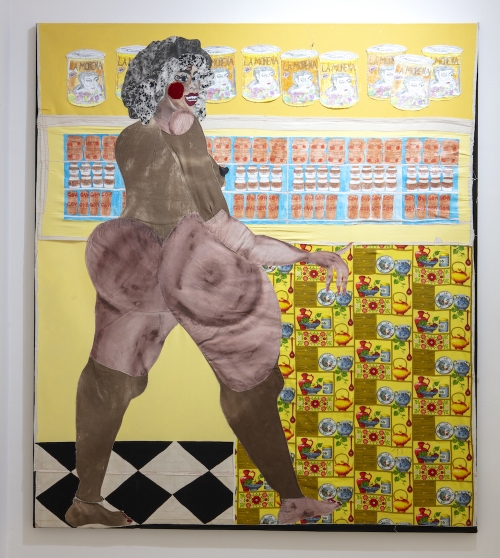

Ol’Bay, 2019

Painted canvas, fabric, digital rendering on canvas, hand-colored photocopy, photocopy, paper, Flashe, gouache, and acrylic

on canvas

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

Ol’Bay illustrates the artist’s broad array of techniques and creative reuse of her prior work. It synthesizes parts of the artist’s own history as it resituates body parts from an earlier painting within the black-and-white checkerboard flooring of the bodega and its dense array of canned food products. The figure’s head, lower arm, and upper legs are photographic reproductions on canvas from Milk Chocolate (2017), one of Self’s character studies from her Bodega Run series. Cans of Goya and La Morena beans and other packaged foods—rendered by way of photocopies and digital drawing—allude to the work’s title: a rendering of Old Bay Seasoning, a spice and herb blend that Self associates with her late mother, as well as with American regional cuisine. The square of fabric at the lower right, patterned with displays of dishes, fruits, and cookware, comes from the same bolt of fabric that her mother used to make curtains for their Harlem home. Self’s stitching creates delicate floral embellishments on the curtain fabric that draws out its botanical motifs, and also holds the woman’s body together.

Milk Chocolate, 2017. Gouache, acrylic, Flashe, fabric, and painted canvas on canvas. 96 × 84 inches (243.8 × 213.4 cm). Rubell Museum, Miami © Tschabalala Self

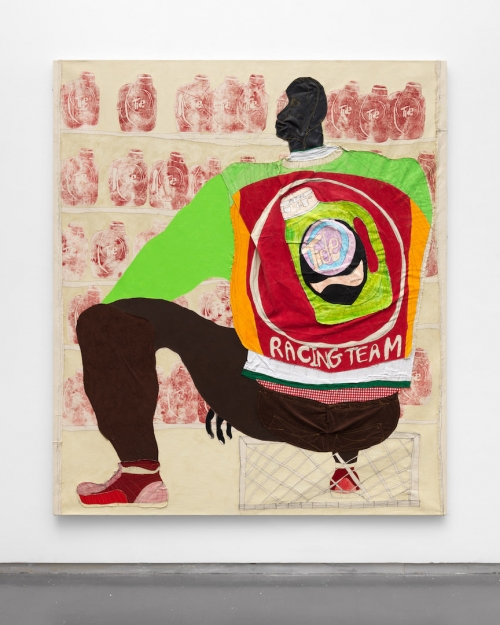

Racer, 2018

Acrylic, watercolor, Flashe, crayon, colored pencil, fabric, and hand-colored canvas on canvas

Collection of Nancy and David Frej

Self is interested in the bodega as a vital public space of social life but also a paradoxical site, where nourishment often exists in its least healthy forms and poverty confronts excess. The man in Racer, sporting a brightly colored racing jacket, sits on a milk crate facing rows of the same brand of laundry detergent that appears on the back of his jacket, a gesture to corporate sponsorship, a culture of cleanliness, and the ubiquity of mass- produced consumer goods. Growing up in Harlem, Self recalls seeing such branded attire repurposed as streetwear, a creative re-appropriation that she identifies with black American culture’s innovative contributions to style, fashion, music, and pop culture. In Racer and Thank You (on view nearby), Self suspends the primary figures in a picture plane between the bodega’s shelves and the viewer, an approach to constructing her paintings influenced, in part, by the American artist Romare Bearden, whose photocollages of urban street scenes presented figures and crowds against graphic backdrops.

Romare Bearden, The Dove, 1964. Cut-and-pasted photo reproductions and paper, gouache, pencil, and colored pencil on cardboard. 13 ⅜ × 18 ¾ in. (34 × 47.6 cm.). Blanchette Rockefeller Fund (377.1971). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York. Art © Romare Bearden Foundation/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

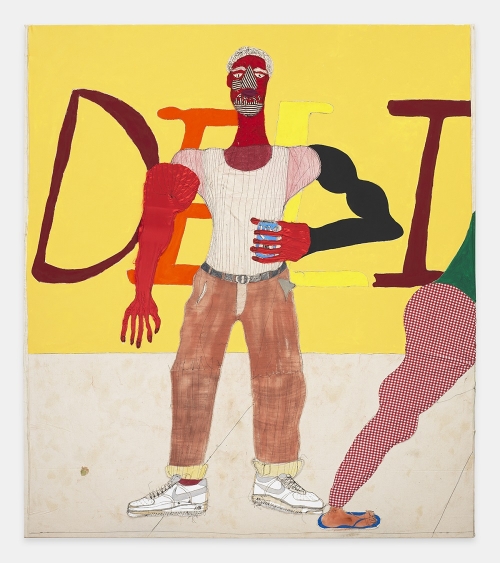

Lite, 2018

Acrylic, Flashe, milk paint, fabric, and gum on canvas

Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston, acquired through the generosity of the Acquisitions Circle, Tristin and Martin Mannion, Rob Larsen, Patrick Planeta and Santiago Varela, and anonymous donors

In 2017, Self began a project titled Bodega Run centered on the people, products, and everyday activities that make up the ubiquitous urban corner store. Lite is exemplary of her expanded interests from the interior of the bodega to the street scenes and interactions adjacent to it. Self describes the central figure in this painting as a somewhat derelict character, his open can of “lite” beer and turned out pocket suggestive of his state. The character’s omnipresence in the neighborhood is reinforced by the way he blends into the deli’s exterior wall, merging with the store’s signage. A red checkered leg, which wraps around the edge of the canvas, suggests another figure energetically striding past him. “Unnoticed by the woman in the frame,” says Self, “he would most likely go unnoticed if he were a real man in real life. And if not unnoticed—most definitely ignored.” The work thematizes the tension between movement and stasis, between attention and inattention all the while drawing attention to the everyday surfaces of city life, such as the piece of gum stuck to the canvas’ sidewalk.

Shorty, 2019

Steel, sand, chicken wire, denim, polyester fiber, plaster gauze, acrylic, Flashe, and automotive paint

Milkcrate, 2019

Laser cut medium-density fiberboard and automotive paint

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

The sculptures in this gallery push the limits of figuration in Self’s art: they are exercises in taking the body as far into abstraction as possible in order to understand the minimal amount of information required to read it as a body. Shorty began with a pair of the artist’s old jeans that she intuitively transformed through additive sculptural means. It is perched atop another sculpture fabricated in the image of a plastic milk crate. The common milk crate is an all-purpose, inexpensive, and portable shipping and storage bin (the artist uses them to store fabric scraps in her studio), often used for small-scale food deliveries or to hold products for restocking shelves. They appear as a motif in Self’s Bodega series as a symbol of creative repurposing: in Racer (shown nearby), a figure sits atop one. In the sculptures on view here, the milk crate functions as a pedestal or plinth, presenting an ambiguous and partial body as a thing to be revered.

Pocket, 2019

Plaster gauze, mirrored plexiglass, aluminum, polyester fiber, acrylic, Flashe, and automotive paint

Milkcrate, 2019

Laser cut medium-density fiberboard and automotive paint

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

Pant, 2018

Oil, Flashe, acrylic paint, fabric, paper, and exposed thread on canvas

Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Iris and Adam C. Singer

Loner, 2016

Painted canvas, Flashe, acrylic, and colored pencil on canvas

Collection of Craig Robins

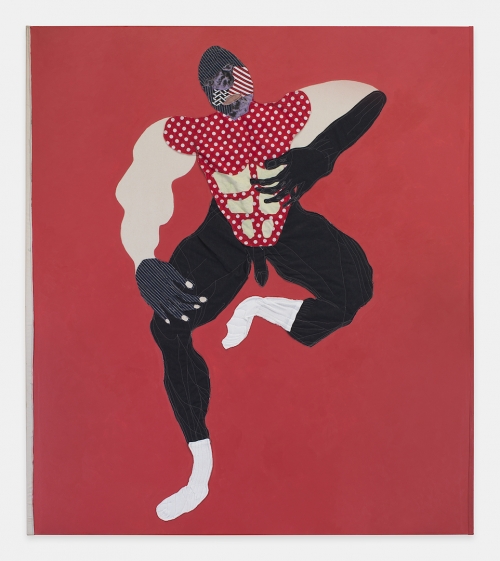

Sock, 2018

Oil, Flashe, acrylic, fabric, and white cotton socks on canvas

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

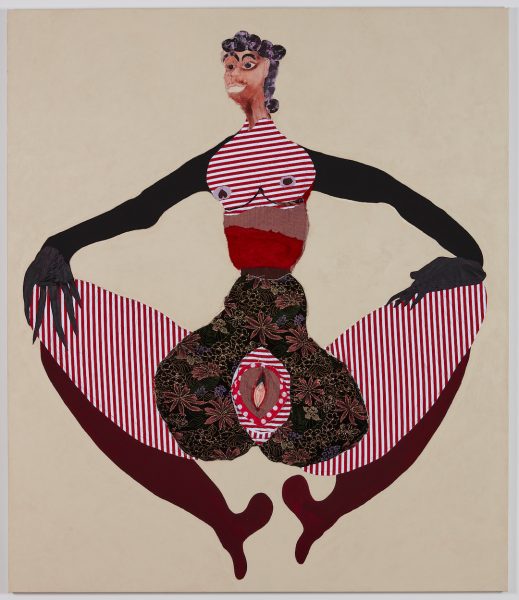

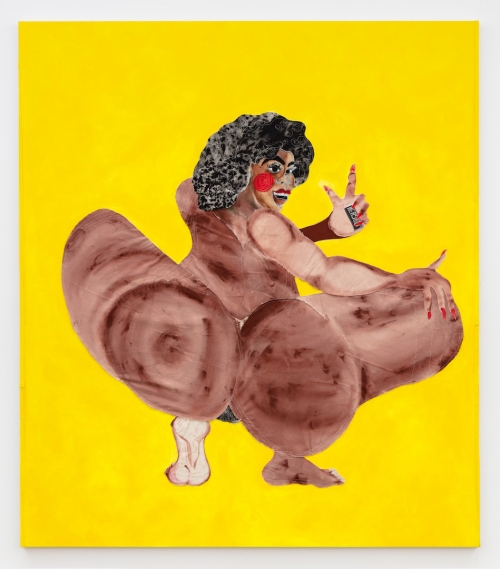

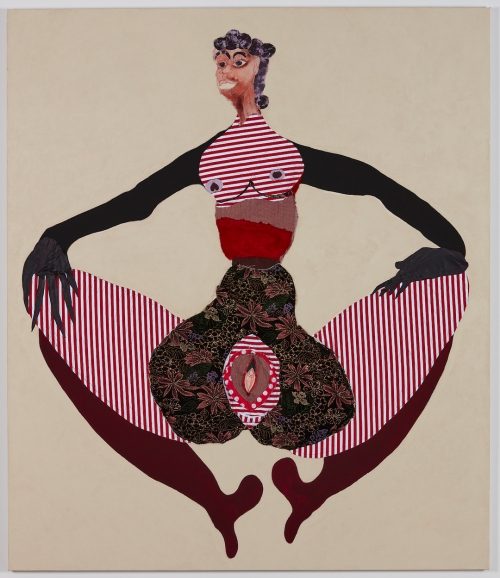

Origin, 2018

Oil, Flashe, acrylic, and fabric on canvas

Courtesy Tschabalala Self Studio

This painting was made in response to the artwork of the American painter Georgia O’Keeffe, who imbued organic forms with an uncanny, often surreal, abstraction. Here, Self combines the sexual independence of the flower, drawing on a language of fertility that O’Keeffe often took as a focal point, with the reproductive symbolism of the female figure, who herself blossoms before us. In Origin, the nude figure’s splayed posture, which forms an infinity loop, suggests the self-perpetuating sexuality of the botanical. Her floral-patterned, pear-shaped pelvis, reveals as its seed a vagina: a connection to the womb and the reproductive capacity of a woman’s body. Red-and- white-striped patterns draw the eye to the figure’s chest, thighs, and fertile core, while textures of chiffon and faux leather suggest a unique personal style. Origin differs in character but shares details with other works in this gallery: for example, the same stripe and polka-dot patterns appear on the figure in Sock (2018), which is equally performative of masculinity. By contrast, the dark figure in Pant (2018), which suggests sexual ambiguity and fluidity, bears only a trace of the striped fabric on their cheek and eyebrow, a single polka dot forming their left eye.

Tschabalala Self: Out of Body is organized by Ellen Tani and Ruth Erickson, Mannion Family Curator.

Tschabalala Self: Out of Body is presented by Max Mara.

This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Additional support is generously provided by Fotene Demoulas and Tom Coté, Ted Pappendick and Erica Gervais Pappendick, The Coby Foundation, Ltd, and the Jennifer Epstein Fund for Women Artists.