In the late 1970s, Laurie Simmons began employing photography as a means of critiquing representations of women in mass media. Simmons drew on childhood memories of her mother and representations of mothers she saw on television in the 1950s to stage imagined domestic tableaux, often with a lone female figurine in the interior of a dollhouse, which she then recorded with photography. These artworks subversively explored the concept of the ideal housewife as a fabricated construct.

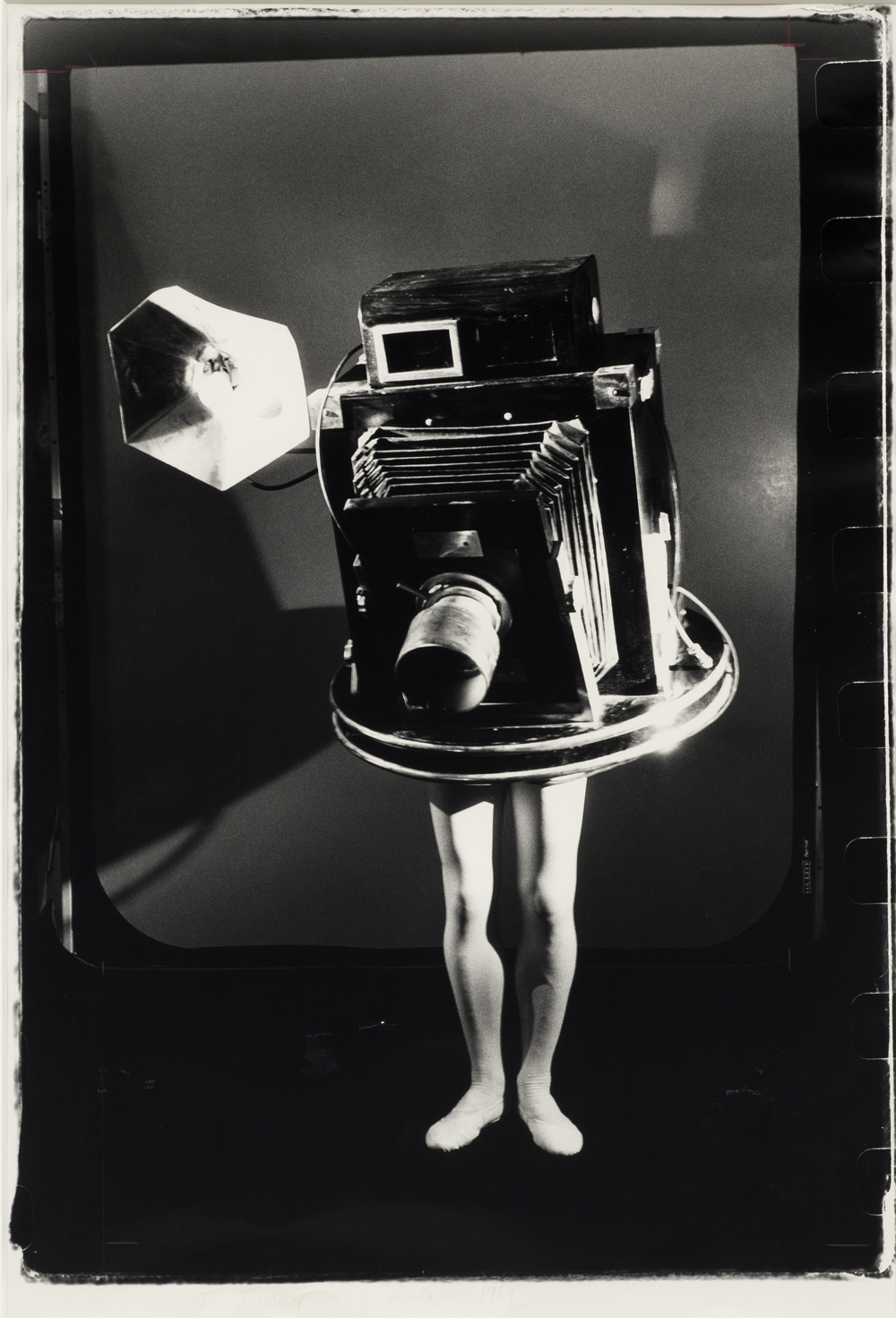

Inspired by packs of dancing cigarettes seen in television commercials and magazine advertisements, Simmons began her Walking Objects series in the late 1980s. She added human legs to books, handbags, cakes, and guns, and then photographed the assemblages at human scale. Often dramatically lit against anonymous backdrops, the Walking Objects anthropomorphize the objects they picture and simultaneously point to the objectification of people, especially women, in contemporary, commodity culture. In Walking Camera (Jimmy the Camera / Gift to Jimmy from Laurie), the prop camera is worn by Simmons’s friend, the artist Jimmy DeSana, a key figure in the East Village art scene in New York in the 1970s and ’80s, who taught Simmons how to develop film. Here, it is DeSana who literally embodies the camera and likewise photography. The enlarged scale of the photographed camera, and its mobility on legs, points toward the ubiquity of photography in everyday life. The photograph also serves as a memorial to DeSana who died of HIV/AIDS-related illnesses in 1990.

This photograph adds depth to the museum’s photography collection, joining key works by Jimmy DeSana, Cindy Sherman, and Louise Lawler. Simmons’s studio-based photography is also a key precedent for artist’s in the collection, including Roe Ethridge, Leslie Hewitt, Anne Collier, and Sara VanDerBeek.

2016.21